Incoming Search Terms:

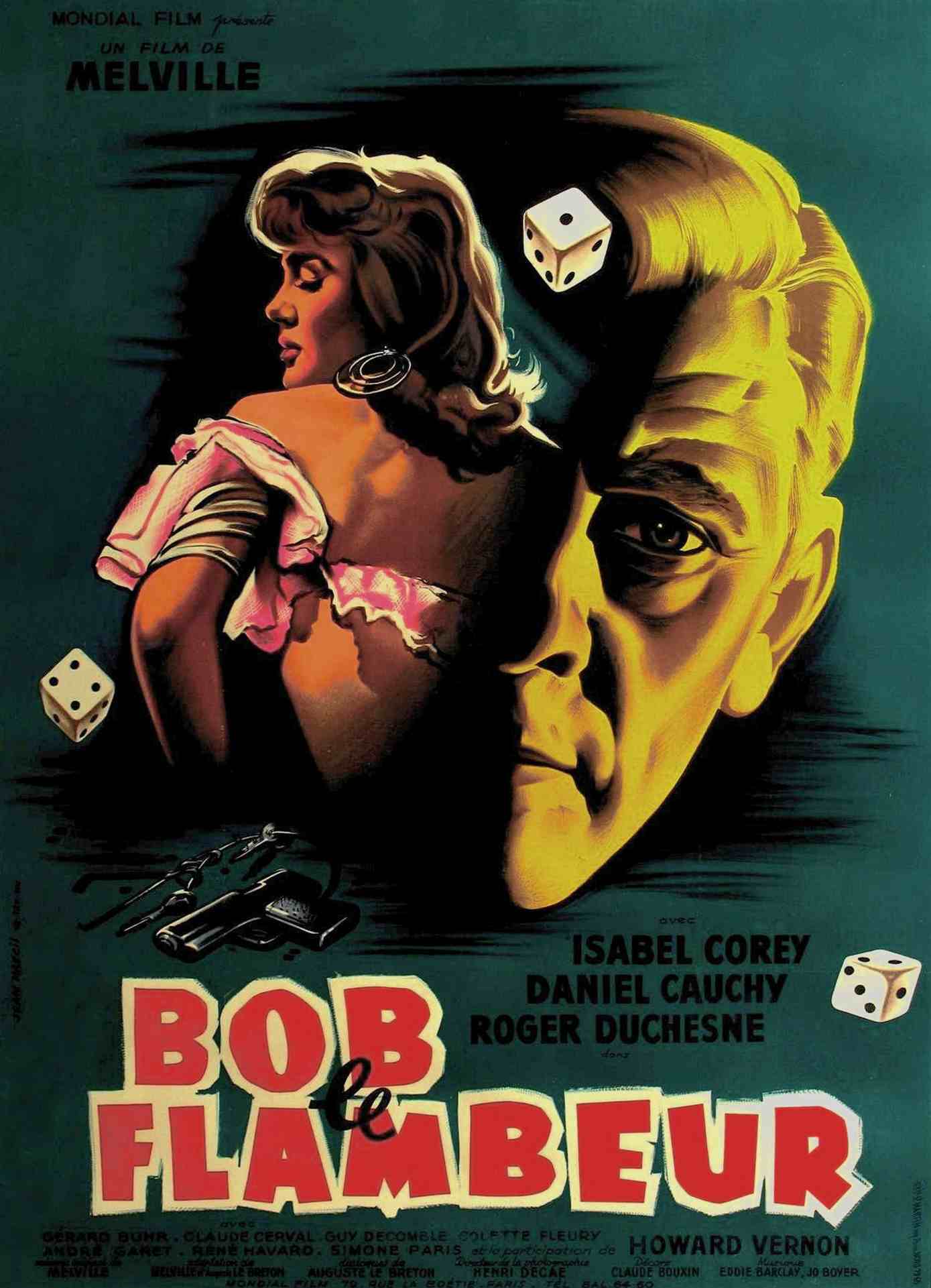

- Bob le flambeur

- Heist film

- Jean-Pierre Melville

- Auguste Le Breton

- Two Men in Manhattan

- Daniel Cauchy

- Roger Duchesne

- List of English-language films with previous foreign-language film versions

- Gérard Buhr

- List of cult films: B

- Simone Paris

- 1956 in film

- Montmartre Funicular

- Guy Decomble

- Howard Vernon

- Isabelle Corey

- René Havard

- List of film director and cinematographer collaborations

- List of film noir titles

- Eddie Barclay

Video 1: Bob le Flambeur (1956) 1956 Full Movie

Video 2: Bob le Flambeur (1956) 1956 Full Movie

![Bob Le Flambeur [1956] - destinationmanager](http://3.bp.blogspot.com/-SbleCcb-aDI/TfkdDYpaqxI/AAAAAAAAFXE/A-Fk5izWox0/s1600/BLF%2BBob%2Bat%2BLe%2BCarpeaux.bmp)

Bob le flambeur GudangMovies21 Rebahinxxi LK21

Plot

Bob is a gambler who lives on his own in the Montmartre district of Paris, where he is well-liked by the demi-monde community. A former bank robber and convict, he has mostly kept out of trouble for the past 20 years, and is even friends with a police commissioner, Ledru, whose life he once saved. Ever the gentleman, Bob lets Anne, an attractive young woman who has just lost her job, stay in his apartment in order to keep her from the attentions of Marc, a pimp he hates. Bob declines Anne's advances, instead steering her to his young protégé Paolo, who soon sleeps with her. Through Jean, an ex-con who is now a croupier at the casino in Deauville, Bob's friend Roger, a safecracker, learns that, by 5:00 in the morning on the day of a big horse race at the nearby track, the casino safe is expected to contain around 800 million French francs in cash, equivalent to a little more than $24,000,000 in 2025. As Bob has had a run of bad luck, he plans to rob the safe, convincing a man named McKimmie to finance the preparations and recruiting a team to carry out the heist. Jean gets detailed floor plans of the casino and the specifications of the safe, and buys a bracelet for his wife, Suzanne, with some of the money he is paid for his services. The smitten Paolo brags to Anne about the upcoming raid to try to impress her. Not taking him seriously, she lets this information slip to Marc just before the two have sex. Earlier, Marc had been arrested by Ledru for beating up one of his prostitutes, but Ledru had released him on the condition that he provide some information on a bigger crime; Marc's reaction makes Anne realize she may have made a mistake. The next morning, Anne tells Bob what she did, and he and Roger search for Marc, but cannot find him. Marc tells Ledru that he has heard about a caper involving Bob, but needs a few more hours to obtain confirmation, so Ledru lets him go. When Bob tells Paolo about Marc and Anne, the young man finds Marc and shoots the man dead just as he is about to tell Ledru what he was able to find out. Meanwhile, Suzanne discovers where her husband got the money to buy the bracelet and decides to ask Bob for a larger share of the take. They drive to Paris, but are unable to find him or Roger. She then persuades Jean to back out of it and anonymously tips off Ledru. Thinking that, with Marc dead, their plan is still a secret, Bob and his team head to Deauville. Ledru searches fruitlessly for Bob to convince him to abandon his plan. He reluctantly leads a convoy of armed police to the casino. Bob enters the casino to check on things. The plan is that, unless he signals them otherwise, his team will burst in at 5:00 a.m. and rob the safe at gunpoint. He had promised Roger that he would not gamble until after the heist was over, but, after wandering around for a while, he cannot resist placing a bet. He has an incredible run of good luck, first at roulette, then at chemin de fer, and loses track of the time. Just before 5:00, he finally looks at his watch. He orders the staff to cash his huge pile of chips and hurries out the door. The police arrive as Bob's team are walking toward the casino, and a shootout ensues; Paolo is shot. Bob comes upon the aftermath and holds Paolo as he dies. He and Roger are handcuffed and put into Ledru's car, and Bob's winnings are put in the trunk. Ledru says Bob will probably only spend three years in prison, but Roger says that, with a good lawyer, he will get acquitted. Bob quips that he may even sue for damages.Principal cast

The voice of the narrator is that of Jean-Pierre Melville.Production

The film was shot on location in Paris and Deauville, with two interiors filmed at Melville's own Studios Jenner. According to an interview, the film cost 17.5 million French francs to produce, though a CNC Censorship file includes an estimate of 32 million French francs.Cinematography

This film was shot by frequent collaborate of Jean-Pierre Melville, Henri Decaë who was the cinematographer on films such as, Elevator to the Gallows (1958), The Boys from Brazil (1978) and The Red Circle (1970). He previously shot le silence de la mer (1949) with Melville and later was cinematographer on Melville's le Samouraï (1967). They eventually split ways due to creative differences but Melville once said of Decaë "exactly shar[ed] my tastes for all things cinema." With his films such as Elevator to the Gallows (1958) Henri Decaë first established his trademark that follows him through his career which is the use of natural lighting. Much like how he lit Jeanne Moreau in Elevator to the Gallows (1958) "with only the available light from shop windows and neon signs." Due to this use of heavily stylized light many critics have traced a connection to the American film noir movement. This film was influential on the French New Wave Movement for many reasons, including visual style. This can be attributed to the fact that Henri Decaë's cinematography caught the attention of Cahiers Du Cinema editors. This secured him a job as cinematographer for influential New Wave films like François Truffaut's The 400 Blows.Release

Released in Paris on 24 April 1956, Bob le flambeur took in 221,659 admissions in Paris and 716,920 admissions in France as a whole, and was Melville's lowest-grossing film at that point in his career.Critical reception

Vincent Canby, writing for The New York Times in 1981, noted that "Melville's affection for American gangster movies may have never been as engagingly and wittily demonstrated as in Bob le flambeur, which was only the director's fourth film, made before he had access to the bigger budgets and the bigger stars (Jean-Paul Belmondo, Alain Delon) of his later pictures." The film received positive reviews when it was re-released by Rialto Pictures in U.S. cinemas in 2001. Roger Ebert added it to his Great Movies list in 2003. Jean-Pierre Melville is often considered a significant figure in the New Wave film movement, credited with inspiring key elements in the movement through his film Bob le flambeur (1956). His work notably influenced Jean-Luc Godard's Breathless. The New Wave was a product of the French reimagining of American cinema, and Melville's contributions provided significant inspiration for this innovative and revolutionary approach to filmmaking, which included the use of location shooting, the handheld camera, and the jump cut. Godard, influenced by Melville's avant-garde style, fully embraced these trends in his filmmaking. "Breathless" was shot entirely on location, featuring dynamic jump cut editing and utilizing a handheld camera. This is a testament to the lasting influence of Melville's pioneering contributions on the evolving landscape of cinema during the New Wave era.[1] Melville understands that in a gangster film, the criminal will ultimately be caught. Bob is less interested in stealing the money itself, yet more interested in everyone knowing who's robbing the bank. He explains the trope that not all gamblers are lucky, yet the idea of losing a gamble is all to be expected. On Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds an approval rating of 97%, based on 30 reviews, with an average rating of 8.1/10; the website's critical consensus reads: "Majorly stylish, Bob le flambeur is a cool homage to American gangster films and the presage to French New Wave mode of seeing."Remake and influence

The Good Thief, an English-language remake of the film written and directed by Neil Jordan, was released in 2002. Bob le flambeur also has influenced such films as the two versions of the American film Ocean's Eleven (1960 and 2001) and Paul Thomas Anderson's Hard Eight (1996).References

= Sources

=External links

Bob le flambeur at IMDb Bob le flambeur at Rotten Tomatoes Bob le flambeur an essay by Lucy Sante at the Criterion Collection "Bob le flambeur", Senses of Cinema, February 2003, Brian FryeBob le Flambeur (1956) – Di Paris, Bob Montagne identik dengan perjudian — dan kemenangan. Ia baik hati, berkelas, dan disukai hampir semua orang di kota, termasuk inspektur polisi Ledru. Namun, ketika nasib Bob memburuk, ia mulai kehilangan teman-temannya dan melakukan pertaruhan paling nekat dalam hidupnya: merampok kasino Deauville selama akhir pekan Grand Prix, saat brankas penuh. Sayangnya, Bob segera mengetahui bahwa permainan itu curang dan polisi sedang mengejarnya. Bob le Flambeur (1956)

Bob le Flambeur

Daftar Isi

- Bob le flambeur - Wikipedia

- Bob le Flambeur (1956) - IMDb

- Bob le Flambeur movie review & film summary (1955) - Roger Ebert

- Bob le flambeur (1956) - The Criterion Collection

- Bob Le Flambeur (1956) - 4K UHD Review - Home Theater Forum

- Bob le Flambeur streaming: where to watch online? - JustWatch

- Bob le Flambeur (1956) directed by Jean-Pierre Melville - Letterboxd

- Bob le flambeur | Current | The Criterion Collection

- Bob le Flambeur: Synopsis and Analysis - Jotted Lines

- BOB LE FLAMBEUR - Film Forum

Bob le flambeur - Wikipedia

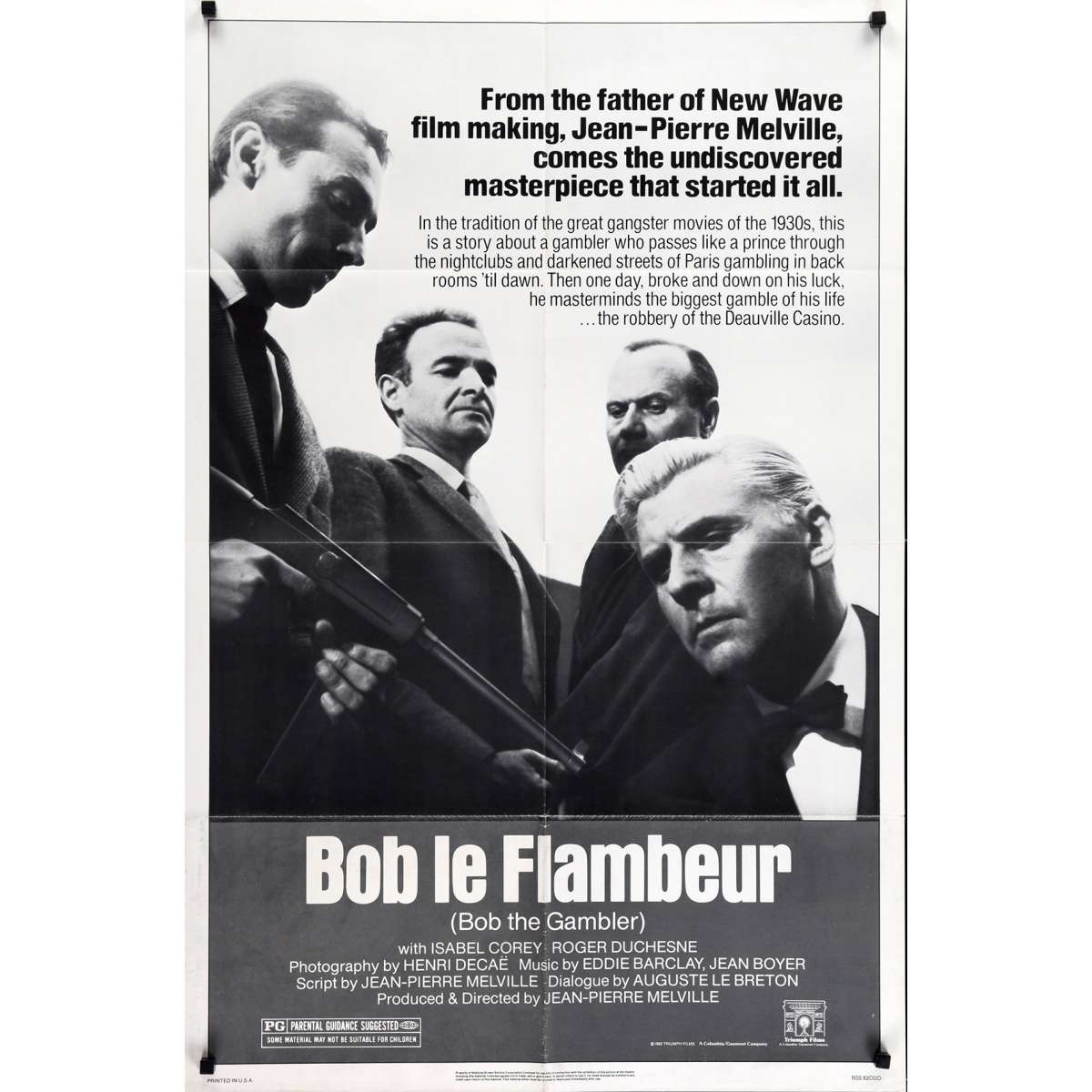

Bob le flambeur (English translation": "Bob the Gambler" or "Bob the High Roller") is a 1956 French heist gangster film directed by Jean-Pierre Melville and starring Roger Duchesne as Bob. It is often considered both a film noir and a precursor to the French New Wave , the latter because of its use of handheld camera and a single jump cut .

Bob le Flambeur (1956) - IMDb

Bob le Flambeur: Directed by Jean-Pierre Melville. With Isabelle Corey, Daniel Cauchy, Roger Duchesne, Guy Decomble. After losing big, an aging gambler decides to assemble a team to rob a casino.

Bob le Flambeur movie review & film summary (1955) - Roger Ebert

May 25, 2003 · Jean-Pierre Melville’s “Bob le Flambeur” (1955) has a good claim to be the first film of the French New Wave.

Bob le flambeur (1956) - The Criterion Collection

Suffused with wry humor, Jean-Pierre Melville’s Bob le flambeur melds the toughness of American gangster films with Gallic sophistication to lay the road map for the French New Wave.

Bob Le Flambeur (1956) - 4K UHD Review - Home Theater Forum

Aug 13, 2024 · Jean-Pierre Melville’s Bob le flambeur (Bob the Gambler), his fourth narrative feature, works well as a bridge between American-inspired French film noir (like Rififi and Elevator to the Gallows) and the New Wave that was about to take the world by storm.

Bob le Flambeur streaming: where to watch online? - JustWatch

Find out how and where to watch "Bob le Flambeur" on Netflix and Prime Video today - including free options.

Bob le Flambeur (1956) directed by Jean-Pierre Melville - Letterboxd

Feb 21, 2004 · Bob served time, but now he’s out and that’s all behind him. His life is a good one: sleep by day, drink and gamble by night. But when his luck deserts him, and his money runs out, he assembles a team to rob the Deauville Casino. Bob Le Flambeur has the nouvelle vague written all over it.

Bob le flambeur | Current | The Criterion Collection

Bob le Flambeur may be the most elegantly rigorous movie ever made about a cockeyed heist. It is also one of the most elegiac, with a twilight mood about it. Bob, as courtly and dignified as any all-night gambler ever was but willing to risk his serenity for one last big score, is in Melville’s view a relic of a bygone, pre-war world, when ...

Bob le Flambeur: Synopsis and Analysis - Jotted Lines

Jun 24, 2019 · Synopsis: Bob is an ageing, former gangster turned gambler in Montmartre (Paris), leading a pleasant if unconventional life with his friend Roger, his protégé, Paolo, and a young woman, Anne, who he has picked up on the street and who he helps out.

BOB LE FLAMBEUR - Film Forum

(1955) Through the night streets of Montmartre saunters silver-haired Bob Montagné (Roger Duchesne), ex-gangster and, as per his nickname, a “flambeur” (high roller, or compulsive gambler), moving from poker to craps to the track to roulette to baccarat and back, at the break of dawn, to the one-armed bandit he keeps in his posh pad.