- Source: Dracula

- Drakula

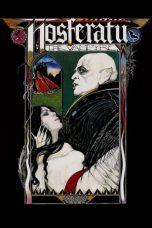

- Nosferatu

- Dracula (novel)

- Vlad Ţepeş

- Nosferatu (film 2024)

- Dracula (film 1992)

- Dracula (film berbahasa Inggris 1931)

- Bacelarella dracula

- Vampir

- Kid Dracula

- Dracula

- Bram Stoker's Dracula (1992 film)

- Count Dracula

- Brides of Dracula

- Dracula Untold

- Castlevania

- Dracula (Castlevania)

- Castlevania: Rondo of Blood

- Dracula 2000

- Dracula (1931 English-language film)

Hotel Transylvania 3: Summer Vacation (2018)

Monster Mash (2024)

The Last Voyage of the Demeter (2023)

Artikel: Dracula GudangMovies21 Rebahinxxi

Dracula is a 1897 Gothic horror novel by Irish author Bram Stoker. An epistolary novel, the narrative is related through letters, diary entries, and newspaper articles. It has no single protagonist and opens with solicitor Jonathan Harker taking a business trip to stay at the castle of a Transylvanian nobleman, Count Dracula. Harker escapes the castle after discovering that Dracula is a vampire, and the Count moves to England and plagues the seaside town of Whitby. A small group, led by Abraham Van Helsing, attempt to kill him.

Dracula was mostly written in the 1890s. Stoker produced over a hundred pages of notes for the novel, drawing extensively from Transylvanian folklore and history. Some scholars have suggested that the character of Dracula was inspired by historical figures including the Wallachian prince Vlad the Impaler and the Countess Elizabeth Báthory, but recent scholarship suggests otherwise and Stoker's notes mention neither by name. He probably found the name Dracula in Whitby's public library while on holiday, and selected it because he thought it meant "devil" in Romanian.

Following publication on 26 May 1897, Dracula was considered a frightening work by positive and negative reviewers. Comparisons were made to other Gothic fiction, with many noting its structural similarity to Wilkie Collins' The Woman in White (1859). In the 20th century, Dracula became regarded as a seminal work of Gothic fiction. Scholars explore the novel within the historical context of the Victorian era and discuss its portrayal of gender, sexuality, religion, and race.

Dracula is one of the most famous works of English literature. The book's characters have entered popular culture as archetypal versions of their characters: Count Dracula as the quintessential vampire, and Van Helsing as the most iconic vampire hunter. The novel, which is in the public domain, has been adapted for film over 30 times, and its characters have made numerous appearances in virtually all forms of media.

Plot

Jonathan Harker, a newly qualified English solicitor, visits Count Dracula at his castle in the Carpathian Mountains to help the Count purchase a house near London. Ignoring the Count's warning, Harker wanders the castle at night and encounters three vampire women; Dracula rescues Harker, and gives the women a small child bound inside a bag. Harker awakens in bed; soon after, Dracula leaves the castle, abandoning him to the women. Harker escapes and ends up delirious in a Budapest hospital. Dracula takes a ship called the Demeter for England with boxes of earth from his castle. The captain's log narrates the crew's disappearance until he alone remains, bound to the helm to maintain course. An animal resembling a large dog is seen leaping ashore when the ship runs aground at Whitby.

Lucy Westenra's letter to her best friend, Harker's fiancée Mina Murray, describes her marriage proposals from Dr. John Seward, Quincey Morris, and Arthur Holmwood. Lucy accepts Holmwood's, but all remain friends. Mina joins Lucy on holiday in Whitby. Lucy begins to sleepwalk. After Dracula's ship lands in Whitby, he stalks Lucy. Mina receives a letter about her missing fiancé's illness, and goes to Budapest to nurse him. Lucy becomes very ill. Seward's old teacher, Professor Abraham Van Helsing, determines the nature of Lucy's condition, but refuses to disclose it. He diagnoses her with acute blood-loss. Van Helsing places garlic flowers around her room and makes her a necklace of them. Lucy's mother removes the garlic flowers, not knowing they repel vampires. While Seward and Van Helsing are absent, Lucy and her mother are terrified by a wolf and Mrs. Westenra dies of a heart attack; Lucy dies shortly thereafter. After her burial, newspapers report children being stalked in the night by a "bloofer lady" (beautiful lady), and Van Helsing deduces it is Lucy. The four go to her tomb and see that she is a vampire. They stake her heart, behead her, and fill her mouth with garlic. Jonathan Harker and his now-wife Mina return and join the campaign against Dracula.

Everyone stays at Dr. Seward's asylum as the men begin to hunt Dracula. Van Helsing finally reveals that vampires can only rest on earth from their homeland. Dracula communicates with Seward's patient, Renfield, an insane man who eats vermin to absorb their life force. After Dracula learns of the group's plot against him, he uses Renfield to enter the asylum. He secretly attacks Mina three times, drinking her blood each time and forcing Mina to drink his blood on the final visit. She is cursed to become a vampire after her death unless Dracula is killed. As the men find Dracula's properties, they discover many earth boxes within. The vampire hunters open each of the boxes and seal wafers of sacramental bread inside them, rendering them useless to Dracula. The group fail to trap the Count in his Piccadilly house, and learn that Dracula is fleeing to his castle in Transylvania with his last box. Using hypnosis, Van Helsing exploits Mina's faint psychic connection to Dracula to track his movements and they pursue, guided by Mina.

In Galatz, Romania, the hunters split up. Van Helsing and Mina go to Dracula's castle, where the professor destroys the vampire women. Jonathan Harker and Arthur Holmwood follow Dracula's boat on the river, while Quincey Morris and John Seward parallel them on land. After Dracula's box is finally loaded onto a wagon by Romani men, the hunters converge and attack it. After routing the Romani, Harker decapitates Dracula as Quincey stabs him in the heart. Dracula crumbles to dust, freeing Mina from her vampiric curse. Quincey is mortally wounded in the fight against the Romani. He dies from his wounds, at peace with the knowledge that Mina is saved. A note by Jonathan Harker seven years later states that the Harkers have a son, named Quincey.

Background

= Author

=In a letter to Walt Whitman, Bram Stoker described his own temperament as "secretive to the world", but he nonetheless led a relatively public life. Before Dracula was published, Stoker was already well-known in the theatrical world as the assistant manager of the Lyceum Theatre in London and personal assistant to the stage actor Henry Irving. Stoker supplemented his income from the theatre by writing romance and sensation novels, and had published 18 books by his death in 1912. Dracula was Stoker's seventh published book, following The Shoulder of Shasta (1895) and preceding Miss Betty (1898). Hall Caine, a close friend of Stoker's, wrote an obituary for him in The Daily Telegraph, saying that—besides his biography on Irving—Stoker wrote only "to sell" and "had no higher aims".

= Inspiration

=Folkloric vampires predate Stoker's Dracula by hundreds of years. Stoker adopted some characteristics of folkloric vampires for his own, such as their aversion to garlic and staking as a means of killing them. He invented some attributes—for example, Stoker's vampires must be invited into one's home, sleep on earth from their homeland and have no reflection in mirrors. Sunlight is not fatal to Dracula in the novel—an invention of the unauthorised Dracula film, Nosferatu (1922)—but does weaken him. Some of Stoker's inventions applied unrelated lore to vampires for the first time; for example, Dracula has no reflection because of an folkloric concept that mirrors show the human soul.

Some Irish scholars have suggested Irish folklore as an inspiration for the novel, for example the revenant Abhartach, and the 11th-century High King of Ireland Brian Boru. Dracula scholar Elizabeth Miller notes that in his childhood Stoker was exposed to supernatural tales and Irish oral history involving premature burials and staked bodies.

Count Dracula has literary progenitors. John William Polidori's "The Vampyre" (1819) includes an aristocratic vampire with powers of seduction. The lesbian vampire of Sheridan Le Fanu's Carmilla (1872) can transform into a cat, as Dracula can transform into a dog. Dracula resembles earlier Gothic villains in appearance, with Miller comparing him to the villains of Ann Radcliffe's The Italian (1796) and Matthew Gregory Lewis's The Monk (1796).

There is virtually unanimous consensus that Dracula was inspired, in part, by Henry Irving. Scholars note the Count's tall and lean physique and aquiline nose, with William Hughes specifically citing influence to Irving's performance as Shylock in a Lyceum Theatre performance of The Merchant of Venice. Stoker's contemporaries remarked upon the similarity. Stoker had praised a performance of Irving as "a wonderful impression of a dead man fictitiously alive [with eyes like] cinders of glowing red from out the marble face". Louis S. Warren writes that Dracula was founded on "the fear and animosity his employer inspired in him".

Historical figures have been suggested as inspirations for Count Dracula but there is no consensus. In a 1972 book, Raymond T. McNally and Radu Florescu popularised the idea that Ármin Vámbéry supplied Stoker with information about Vlad Dracula, commonly known as Vlad the Impaler. Their investigation, however, found nothing about "Vlad, Dracula, or vampires" within Vámbéry's published papers, nor in Stoker's notes about their meeting. Miller calls the link to Vlad III "tenuous", indicating that Stoker incorporated a large amount of "insignificant detail" from his research, and rhetorically asking why he would omit Vlad III's infamous cruelty. Likewise, McNally suggested in 1983 that the crimes of Elizabeth Báthory inspired Stoker. A book used by Stoker for research, The Book of Were-Wolves, does contain some information on Báthory, but Stoker never took notes from the short section devoted to her. Miller and her co-author Robert Eighteen-Bisang concur that there is no evidence Elizabeth Bathory inspired Stoker.

Textual history

= Composition

=Prior to writing the novel, Stoker researched extensively, assembling over 100 pages of notes, including chapter summaries and plot outlines. Stoker undertook some of his research at a library at Whitby in the summer of 1890 but most was done at the London Library. The earliest dated notes for Dracula are from 8 March 1890, comprising an outline of a early chapter that, according to Joseph S. Bierman, "differs from the final version in only a few details". In February 1892, Stoker wrote a 27-chapter outline of the novel from which Miller concludes, "all the key pieces of the jigsaw were in place."

Stoker stated that that it took him about three years to write the novel, and it is likely that he wrote most of the manuscript during his summer holidays in Cruden Bay, Scotland from 1893 to 1896. Stoker generally wrote in spare time from his duties as Irving's business manager, and the long gestation of the novel is indicative of the importance he placed on it.

Stoker's notes illuminate much about earlier iterations of the novel. According to Bierman, Stoker always intended to write an epistolary novel but originally set it in Styria instead of Transylvania. The novel's vampire was always intended to be a Count, even before he was given the name Dracula. Stoker took the name Dracula from William Wilkinson's "dry history" of Wallachia and Moldavia (1820), which he probably found in Whitby's public library while holidaying there in 1890. Stoker copied the following footnote from the book: "Dracula means devil. Wallachians were accustomed to give it as a surname to any person who rendered himself conspicuous by courage, cruel actions or cunning".

Stoker's initial plans for Dracula markedly differ from the final novel. Had Stoker completed his original plans, a German professor called Max Windshoeffel "would have confronted Count Wampyr from Styria", and one of the vampire hunters would have been slain by a werewolf. Stoker's earliest notes indicate that Dracula might have originally been intended to be a detective story, with a detective called Cotford and a psychical investigator called Singleton.

= Publication

=Dracula was published in London in May 1897 by Archibald Constable and Company. It cost six shillings, and was bound in yellow cloth and titled in red letters. In 2002, Barbara Belford, a biographer, wrote that the novel looked "shabby", perhaps because the title had been changed at a late stage. Although contracts were typically signed at least six months ahead of publication, Dracula's was unusually signed only six days prior to publication. For the first thousand sales of the novel, Stoker earned no royalties. Following serialisation by American newspapers, Doubleday & McClure published an American edition in 1899. Stoker's mother, Charlotte Stoker, enthused about the novel and predicted it would bring her son immense financial success. She was wrong; the novel, although reviewed well, did not make Stoker much money and did not establish his critical reputation until after his death. Since its publication, Dracula has never been out of print.

Style

= Epistolary structure

=Dracula's structure as an epistolary novel has been somewhat neglected by critics compared to other aspects of the novel. As an epistolary novel, Dracula is narrated through a series of documents. The novel's first four chapters are related as the journals of Jonathan Harker. Scholar David Seed notes that Harker's accounts function as an attempt to translocate the "strange" events of his visit to Dracula's castle into the nineteenth-century tradition of travelogue writing. John Seward, Mina Murray and Jonathan Harker all keep a crystalline account of the period as an act of self-preservation; David Seed notes that Harker's narrative is written in shorthand to remain inscrutable to the Count, protecting his own identity, which Dracula threatens to destroy. Harker's journal, for example, embodies the only advantage during his stay at Dracula's castle: that he knows more than the Count thinks he does. The novel's disparate accounts approach a kind of narrative unity as the narrative unfolds. In the novel's first half, each narrator has a strongly characterised narrative voice, with Lucy's showing her verbosity, Seward's businesslike formality, and Harker's excessive politeness. These narrative styles also highlight the power struggle between vampire and his hunters; the increasing prominence of Van Helsing's broken English as Dracula gathers power represents the entrance of the foreigner into Victorian society.

= Gothic genre

=Dracula is considered a prototype for the Gothic genre, and the culmination of an era of Stoker and his novel are mentioned within the contexts of Irish Gothic and Urban Gothic. As established by the first Gothic novel The Castle of Otranto, the novel involves the supernatural. Jerrold E. Hogle notes a Gothic tendency to blur boundaries, pointing to sexual orientation, race, class, and even species. He writes that that the Count "can disgorge blood from his breasts" in addition to his teeth; his attraction to both Jonathan Harker and Mina Murray; appearing both racially western and eastern; and character as aristocrat able to mingle with homeless vagrants.

Many of the Count's physical attributes were typical of Gothic villains during Stoker's lifetime. In particular, his hooked nose, pale complexion, large moustache and thick eyebrows were likely inspired by the villains of Gothic fiction. Likewise, Stoker's selection of Transylvania has roots in the Gothic. Writers of the mode were drawn to Eastern Europe as a setting because travelogues presented it as a land of primitive superstitions. Dracula deviates from Gothic tales before it by firmly establishing its time—that being the modern era. The novel is an example of the Urban Gothic subgenre.

Reception

Upon publication, Dracula was well received. Reviewers frequently compared the novel to other Gothic writers, and mentions of novelist Wilkie Collins and The Woman in White (1859) were especially common because of similarities in structure and style. A review appearing in The Bookseller notes that the novel could almost have been written by Collins, and an anonymous review in Saturday Review of Politics, Literature, Science and Art wrote that Dracula improved upon the style of Gothic pioneer Ann Radcliffe. Another anonymous writer described Stoker as "the Edgar Allan Poe of the nineties". Other favourable comparisons to other Gothic novelists include the Brontë sisters and Mary Shelley.

Many of these early reviews were charmed by Stoker's unique treatment of the vampire myth. One called it the best vampire story ever written. The Daily Telegraph's reviewer noted that while earlier Gothic works, like The Castle of Otranto, had kept the supernatural far away from the novelists' home countries, Dracula's horrors occurred both in foreign lands—in the far-away Carpathian Mountains—and at home, in Whitby and Hampstead Heath. An Australian paper, The Advertiser, regarded the novel as simultaneously sensational and domestic. One reviewer praised the "considerable power" of Stoker's prose and describing it as impressionistic. They were less fond of the parts set in England, finding the vampire suited better to tales set far away from home. The British magazine Vanity Fair noted that the novel was, at times, unintentionally funny, pointing to Dracula's disdain for garlic.

Dracula was widely considered to be frightening. A review appearing in The Manchester Guardian in 1897 praised its capacity to entertain, but concluded that Stoker erred in including so much horror. Likewise, Vanity Fair opined that the novel was "praiseworthy" and absorbing, but could not recommend it to those who were not "strong". Stoker's prose was commended as effective in sustaining the novel's horror by many publications. A reviewer for the San Francisco Wave called the novel a "literary failure"; they elaborated that coupling vampires with frightening imagery, such as insane asylums and "unnatural appetites", made the horror too overt, and that other works in the genre, such as The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, had more restraint.

Modern critics frequently write that Dracula had a mixed critical reception upon publication. Carol Margaret Davison, for example, notes an "uneven" response from critics contemporary to Stoker. John Edgar Browning, a scholar whose research focuses on Dracula and literary vampires, conducted a review of the novel's early criticism in 2012 and determined that Dracula had been "a critically acclaimed novel". Browning identified only three as "wholly or mostly negative"; four as "mixed" in their assessment; ten as "generally positive"; and the rest as positive and possessing no negative reservations. Among the positive reviews, Browning writes that 36 were unreserved in their praise, including publications like The Daily Mail, The Daily Telegraph, and Lloyd's Weekly Newspaper. Other critical works have rejected the narrative of Dracula's mixed response. Raymond T. McNally and Radu Florescu's In Search of Dracula mentions the novel's "immediate success". Other works about Dracula, coincidentally also published in 1972, concur; Gabriel Ronay says the novel was "recognised by fans and critics alike as a horror writer's stroke of genius", and Anthony Masters mentions the novel's "enormous popular appeal". Since the 1970s, Dracula has been the subject of significant academic interest; the novel has spawned many nonfiction books and articles, and has a dedicated peer-reviewed journal. The novel's complexity has permitted a flexibility of interpretation, with Anca Andriescu Garcia describing interest from scholars of psychoanalysis, postcolonialism, social class and the Gothic genre.

Context and interpretation

= Sexuality and gender

=Modern critical writings about vampirism widely acknowledge its link to sex and sexuality. As a result, sexuality and seduction are two of the novel's most frequently discussed themes. Across the novel's critical history, theorists have collectively argued that the Count breaks virtually "every Victorian taboo", for example non-procreative sex (including fellatio), transgressive sexuality, homosexuality and bisexuality.

Transgressive or abnormal sexuality within Dracula is a broad topic. Some psychosexual critics focus on the disruption of Victorian gender roles; within the Victorian context, the male has "the right and responsibility of vigorous appetite" while the woman must "suffer and be still". Critics highlight the many places in which the novel disrupts these social mores: Jonathan Harker is excited by the prospect of being penetrated; Dracula's resulting anger and jealousy; and Lucy's transformation into a sexually aggressive predator who drains "vital fluid". Some critics, including professor Carol Senf, argue that the novel reflects anxiety about female sexual awakening as a threat to established norms.

Dracula contains no overt homosexual acts, but homosexuality or homoeroticism is a theme discussed by critics. Christopher Craft argues that the primary threat Dracula poses is that he will "seduce, penetrate, [and] drain another male", and reads Harker's excitement to submit as a proxy for "an implicitly homoerotic desire". Some critics note that changes made to the 1899 American version of the text reinforce this subtext, wherein Dracula states he will feed on Harker. Critics have variously linked these themes to homoerotic letters Stoker wrote to Walt Whitman, his friendship with Oscar Wilde, his intensely emotional relationship with Irving, and contemporary rumours of Stoker's almost sexless marriage. David J. Skal acknowledged the letters' subtext but cautioned against applying anachronistic modern sexual labels to Stoker.

Critics discuss the depiction of gender within the context of Stoker's views and his cultural context. The New Woman phenomenon was a late-Victorian term describing an emerging class of women with greater social, sexual and economic control over their lives. Several critics describe the battle against Dracula as a fight for control over women's bodies. Senf suggests that Stoker was ambivalent about the New Woman phenomenon, while Signorroti argues that the novel's discomfort with female sexual autonomy refects Stoker's dislike for the movement. Both Lucy and Mina have characteristics associated with the New Woman, but Mina, who plays an important role in Dracula's defeat, expresses contempt for the concept. Senf writes that Lucy, however, is punished for expressing dissatisfaction with her social position as a woman, destroying the vampire and "reestablishing male supremacy".

= Race

=Dracula, and specifically the Count's migration to Victorian England, is frequently read as emblematic of invasion literature, and a projection of fears about racial pollution. Stephen Arata describes the novel's cultural context of mounting anxiety in Britain over the decline of the British Empire, the rise of other world powers, and a "growing domestic unease" over the morality of imperial colonisation. Arata regards the novel as an instance of "reverse colonisation": fear of other races invading England and weakening its racial purity. Patricia McKee writes that Dracula represents a negation of white culture while Mina Harper represents "pure whiteness". Dracula can be said to both kill white bodies and turn them into the racial Other in death. Some critics connect the racialisation of Dracula to his depiction as a degenerate criminal.

Critics frequently identify antisemitic themes and imagery in the novel. Between 1891 and 1900, the number of Jews living in England increased sixfold, mainly due to antisemitic legislation and pogroms in eastern Europe. Examples cited by Jack Halberstam of antisemitic connections include Dracula's appearance, wealth, parasitic bloodlust, and "lack of allegiance" to one country. Dracula's appearance may resembles some other cultural depictions of Jews, such as Fagin in Charles Dickens's Oliver Twist (1838), and Svengali of George du Maurier's Trilby (1895). Jewish people were frequently described as parasites in Victorian literature; Halberstam highlights fears that Jews would spread diseases of the blood, and one journalist's description of Jews as "Yiddish bloodsuckers". Daniel Renshaw writes that Dracula is not himself Jewish and that the novel represents a general suspicion of all foreigners. He argues that any antisemitism is "semi-subliminal" and mainly reflects the 19th-century antisemitic conception of Jewish people.

The novel's depiction of Slovaks and Romani people has attracted limited scholarly attention. In the novel, Harker describes the Slovaks as "barbarians" and their boats as "primitive", reflecting his imperialistic condescension towards other cultures. Peter Arnds writes that the Count's control over the Romani and his abduction of young children evoke folk superstitions about Romani people stealing children, and that his ability to transform into a wolf is related to xenophobic beliefs about the Romani as animalistic. Croley argues that Dracula's association with the Romani made him suspect in the eyes of Victorian England, where they were stigmatised owing to beliefs that they ate "unclean meat" and lived among animals.

= Religion, superstition and science

=Dracula is saturated with religious imagery. Christopher Herbert regards the novel as a parable about conflict with an enemy who opposes Christ and Christianity. Scholars discuss the novel's depiction of religion in relation to late Victorian anxieties about the threat which secularism, scientific rationalism and the occult posed to Christian beliefs and morality. Stoker himself had a lifelong interest in supernatural inquiry, and Herbert writes that he mixes the supernatural and superstitious beliefs with religious elements, resulting in metaphors about moral uncleanness becoming literal elements of the text's "occult reality". Herbert notes that the blood of Christ is important to Christian ritual and imagery, and Richard Noll notes that actual consumption of human blood is one of the oldest Judeo-Christian taboos.

The vampire hunters use many weapons—including Christian practices and symbols (prayer, crucifixes and consecrated hosts), folkloric practices (garlic, staking and decapitation) and contemporary technology (typewriters, phonographs, telegrams, blood transfusions and Winchester rifles)—in their battle against Dracula. Sanders argues that Stoker presents Christianity as a religion that can be instrumentalised and incorporated into scientific knowledge. Herbert describes Van Helsing's "Christian purification" of Lucy as punitively addressing her promiscuity, and the resulting framing of Christianity as a means towards the "eradication of deviancy".

= Political and economic

=Critics discuss the novel in relation to British imperialism and Irish nationalism. Considerable debate exists over whether Dracula is an Irish novel. While largely set in England, Stoker was born in British-ruled Ireland and lived there for the first 30 years of his life. The author was from a Protestant family but he was distanced from its more conservative factions.

Ralph Ingelbien notes that "recognizably nationalist" critics like Terry Eagleton and Seamus Deane favoured readings of Dracula as "a bloodthirsty caricature of the aristocratic landlord" where the vampire represents the death of feudalism. Bruce Stewart changes the focus to the lower classes, suggesting Dracula and his Romani followers more likely represented violence by Irish National Land League activists. Michael Valdez Moses compares Dracula to the disgraced Charles Stewart Parnell, leader of the Irish Home Rule movement. Robert Smart argues that Stoker's experience during the Great Famine (1845–1852) influenced the novel, with Stewart also noting this as historical context.

Many critics observe Count Dracula's noble title and status as an aristocrat. Franco Moretti writes that he is an aristocrat "only in a manner of speaking", citing his lack of servants, simple clothing, and lack of aristocratic hobbies. Moretti suggests that the Dracula's blood thirst represents capital's desire to accumulate more capital. More generally, Moretti argues the novel evinces cultural anxiety about foreign capitalist monopolies functioning as a return of feudalism. Chris Baldick maintains this line of analysis, describing Dracula as an undead symbol of feudalism but concluding that the novel is more concerned with "sexual and religious terrors". Mark Neocleous writes that Dracula symbolises the victory of the bourgeoisie over feudalism. In Das Kapital, Karl Marx compares the bourgeoisie's exploitation of workers to a vampire draining blood. He uses vampires as a metaphor three times in Das Kapital, but these predate the writing of Dracula.

= Disease

=Some scholars contend that the novel's depiction of vampirism symbolises Victorian anxieties about disease. Vampirism could be said to symbolise both an initial infection and the resulting illness. The novel's characters characterises vampirism with terms from social degeneration theory, Victorian psychiatry ("alienism"), and anthropology. Social degeneration relates to some Victorian-era beliefs about poor moral character being transmissible. Sexually transmitted infection, particularly syphilis, is a frequent topic. Stoker's grand-nephew provides evidence that Stoker died from syphilis, suggesting that the infection's slow progress meant Stoker could have contracted it while writing the novel. Brian Aldiss writes that, if, Count Dracula represents the disease itself and Renfield's madness is a symptom of advanced infection. Stoker uses an asylum as a setting, and includes a patient, a psychiatrist and another doctor as characters.

Legacy

= Adaptations

=The story of Dracula has been the basis for numerous adaptations. Stoker himself wrote the first theatrical adaptation (Dracula, or The Undead); it was performed only once—at the Lyceum Theatre in May 1897, before the novel's publication—to secure Stoker's copyright for future adaptations. The manuscript was believed lost, but the British Library possess extracts of the novel's galley proof containing Stoker's handwritten stage directions and dialogue attribution.

There were translations in other languages during Stoker's lifetime. One was serialised in a Swedish newspaper from June 1899 to February 1900 as Mörkrets Makter ("Powers of Darkness"). The serialisation is almost twice as long as Stoker's novel, and contains characters and narrative elements included in Stoker's notes but not in his published novel. The adaptation contains an author's preface signed "B. S", which Eighteen-Bisang and Miller conclude was not written by Stoker. The Swedish translation was rediscovered and republished in 2017. In 1901, Valdimar Ásmundsson translated a heavily abridged version of the Swedish adaptation into Icelandic under the title Makt Myrkranna ("Powers of Darkness"). The translation included an abridged author's preface, purportedly by Stoker. Scholars had known about the existence of the Icelandic adaptation since the 1980s because of Stoker's preface, considering it to be genuine until the Swedish translation was rediscovered.

The first film to feature Count Dracula was Károly Lajthay's Drakula halála (transl. The Death of Dracula), a Hungarian silent film that premiered in 1921—this release date has been questioned by some scholars. Very little of the film survives, and David J. Skal notes that the cover artist for the 1926 Hungarian edition of the novel was more influenced by the second adaptation of Dracula, F. W. Murnau's Nosferatu (1922). Critic Wayne E. Hensley writes that the narrative of Nosferatu differs significantly from the novel, but that characters have clear counterparts. Bram Stoker's widow, Florence, initiated legal action against Prana, the studio behind Nosferatu. The legal case lasted two or three years, with Prana agreeing to destroy all copies in May 1924.

Visual representations of the Count have changed significantly over time. Early treatments of Dracula's appearance were established by theatrical productions in London and New York. Later prominent portrayals of the character by Béla Lugosi (in a 1931 adaptation) and Christopher Lee (firstly in the 1958 film and later its sequels) built upon earlier versions. Chiefly, Dracula's early visual style involved a black-red colour scheme and slicked back hair. Lee's portrayal was overtly sexual, and also popularised fangs on screen. Gary Oldman's portrayal in Bram Stoker's Dracula (1992), directed by Francis Ford Coppola and costumed by Eiko Ishioka, established a new default look for the character—a Romanian accent and long hair. The assortment of adaptations feature many different dispositions and characteristics of the Count.

Dracula has been adapted a large number of times across virtually all forms of media. John Edgar Browning and Caroline Joan S. Picart write that the novel and its characters have been adapted for film, television, video games and animation over 700 times, with nearly 1000 additional appearances in comic books and on the stage. Roberto Fernández Retamar deemed Count Dracula—along with characters such as Frankenstein's monster, Mickey Mouse and Superman—to be a part of the "hegemonic Anglo-Saxon world['s] cinematic fodder". Across the world, completed new adaptations can be produced as often as every week.

= Influence

=Dracula is one of the most famous and influential works of English literature. It was not the first novel to depict vampires, but dominates both popular and scholarly treatments of vampire fiction. Count Dracula is the first character to come to mind when people discuss vampires. Dracula succeeded by drawing together folklore, legend, vampire fiction and the conventions of the Gothic novel. Wendy Doniger described the novel as vampire literature's "centrepiece, rendering all other vampires BS or AS". It profoundly shaped the popular understanding of how vampires function, including their strengths, weaknesses, and other characteristics. Bats had been associated with vampires before Dracula as a result of the vampire bat's existence—for example, Varney the Vampire (1847) included an image of a bat on its cover illustration. But Stoker deepened the association by making Dracula able to transform into one. That was, in turn, quickly taken up by film studios looking for opportunities to use special effects. Patrick McGrath notes that many of the Count's characteristics have been adopted by artists succeeding Stoker in depicting vampires, turning those fixtures into clichés. Aside from the Count's ability to transform, McGrath specifically highlights his hatred of garlic, sunlight, and crucifixes. William Hughes writes critically of the Count's cultural omnipresence, noting that the character of Dracula has "seriously inhibited" discussions of the undead in Gothic fiction.

Adaptations of the novel and its characters have contributed to its enduring popularity. Even within academic discussions, the boundaries between Stoker's novel and the character's adaptation across a range of media have effectively been blurred. In the 1930s, Universal Studios initiated development on a Dracula film and it was revealed that Stoker failed to comply with United States copyright law. This prematurely placed the novel into the public domain in the United States. Stoker's error may have contributed to the novel's enduring status because writers and producers did not need to pay a licence fee to use the character.

Notes and references

= Notes

== References

=Bibliography

= Books

=Further reading

External links

Dracula at Standard Ebooks

Dracula at Project Gutenberg, text version of 1897 edition.

Dracula public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Journal of Dracula Studies

Kata Kunci Pencarian:

Artikel Terkait "dracula"

Bram Stoker's Dracula (1992) - IMDb

14 Okt 2012 · Bram Stoker's Dracula: Directed by Francis Ford Coppola. With Gary Oldman, Winona Ryder, Anthony Hopkins, Keanu Reeves. The centuries old vampire Count Dracula …

Count Dracula - Wikipedia

140 rows · Count Dracula (/ ˈ d r æ k j ʊ l ə,-j ə-/) is the title character of Bram …

Dracula (novel by Bram Stoker) - Encyclopedia …

17 Des 2024 · Dracula is a novel by Bram Stoker published in 1897. Derived from vampire legends, it became the basis for an entire genre of literature and film. It follows the vampire Count Dracula from his castle in Transylvania to England, …

Dracula: Study Guide - SparkNotes

Bram Stoker’s Dracula, published in 1897, is a quintessential Gothic novel that has left an indelible mark on the vampire genre. It is also an epistolary novel with a narrative conveyed through …

Dracula by Bram Stoker - Project Gutenberg

30 Mei 2014 · "Dracula" by Bram Stoker is a Gothic novel written in the late 19th century. The story follows Jonathan Harker, a solicitor’s clerk, who travels to Transylvania to assist Count Dracula with a real estate transaction in England.

Dracula by Bram Stoker - Goodreads

Dracula is a spooky story which begins with Jonathan Harker, an attorney who travels to Transylvania to help his client, Count Dracula, purchase a home in London. However, Dracula is behaving strangely.

Dracula (TV Series 2013–2014) - IMDb

Dracula: Created by Cole Haddon. With Jonathan Rhys Meyers, Jessica De Gouw, Thomas Kretschmann, Victoria Smurfit. Dracula travels to London, with dark plans for revenge against those who ruined his life centuries earlier.

Dracula: Full Book Summary - SparkNotes

Jonathan Harker, a young English lawyer, travels to Castle Dracula in the Eastern European country of Transylvania to conclude a real estate transaction with a nobleman named Count …

Watch Dracula | Netflix Official Site

The Count Dracula legend transforms with new tales that flesh out the vampire's gory crimes -- and bring his vulnerability into the light. Watch trailers & learn more.