- Source: Film censorship in China

- Gone with the Bullets

- Kung Fu Hustle

- Zhang Xinsheng (film)

- Tencent

- ? (film)

- Penyensoran Winnie-the-Pooh di Tiongkok

- My Name Is Khan

- Eternity in Flames

- Minecraft

- Laksmi Pamuntjak

- Film censorship in China

- Censorship in China

- Censorship of Winnie-the-Pooh in China

- Internet censorship in China

- Film censorship

- Music censorship in China

- Blood censorship in China

- Chinese censorship abroad

- List of TV and films with critiques of Chinese Communist Party

- List of films banned in China

Kabayo (2023)

Deliver Us (2023)

Terrifier 2 (2022)

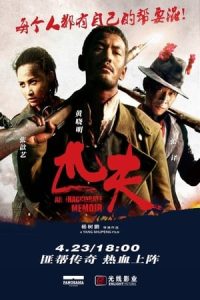

Eastern Bandits (2012)

Artikel: Film censorship in China GudangMovies21 Rebahinxxi

Film censorship in China involves the banning of films which are deemed unsuitable for release and it also involves the editing of such films and the removal of content which is objected to by the governments of China. In April 2018, films were reviewed by the China Film Administration (CFA) under the Publicity Department of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) which dictates whether, when, and how a movie gets released. The CFA is separate from the National Radio and Television Administration under the State Council.

History

= 1923 to 1949

=The beginning of film censorship in China came in July 1923, when the "Film Censorship Committee of the Jiangsu Provincial Education Association" was established in Jiangsu. The committee set out specific requirements for film censorship, such as that films must be submitted for review, and that films that failed to pass must be deleted and corrected, or else they would not be allowed to be screened. However, since the committee was a non-government organization and was mostly composed of educators, film makers did not comply with the requirements, which made film censorship ineffective.: p.7–8

In 1926, after the Hangzhou Film Censorship Board, this was the most specific censorship procedure in recorded history and the first film censorship organization to cooperate fully with the police. The Beijing government also established the Film Censorship Committee in the same year. The censorship included issues of morality and crime, as well as indecency, obstruction of diplomatic relations, and "insult to China". However, the Chinese government is not able to extend its jurisdiction over localities, and the effect of film censorship is limited.: p.7–8

In July 1930, the Nationalist Government established the Film and Drama Censorship Committee in Nanjing. In 1931, the Executive Yuan passed the Film Censorship Law, and the Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Interior of the Nanjing Government jointly established the Film Censorship Committee. In May 1934, the Film Censorship Council was reorganized into the Central Film Censorship Committee, which became the official film censorship Institution.: p.9–10

The 1930s were a period of nationalism in China. Patriotic sentiment was strong in China, and the Kuomintang government often accused foreign films of insulting China. For example, the 1934 release of the American film "Welcome Danger" was accused by Hong Shen of degrading the Chinese and he had a dispute with the cinema manager. The film was eventually banned by the Kuomintang government.: p.9–10

In addition to crimes and insults to China, pornography was also one of banned contents. In 1932, the "Outline of the Enforcement of the Film Censorship Law" had vague and ambiguous provisions: depicting obscene and unchaste acts; depicting those who use tricks or violence against the opposite sex to satisfy their lust; depicting incest directly or indirectly; depicting women undressed and naked in an abnormal manner; depicting women giving birth or abortion. All were prohibited.: p.9–10

In the 1940s, the ROC government sought to prevent the release of Hollywood films which it viewed as insulting to China or Chinese people.

= 1993 to 2017

=In 1993, a preliminary draft of the Film Regulations was sent to film studios throughout China for comments, and the Bureau of Legislative Affairs of the State Council coordinated with the Ministry of Propaganda, the Ministry of Culture, the Ministry of Finance, and the Press and Publication Administration to revise the submitted draft repeatedly. In May 1996, after several discussions, the State Administration of Radio and Television (SARFT) confirmed that the film regulations would be promulgated by the State Council, and on May 29, the Standing Committee of the State Council approved the Film Regulation, which came into effect on July 1, 1996. However, the 1996 film regulations soon failed to keep up with the development of the film industry, and China was actively seeking to join the WTO to comply with the open-door policy. The Ministry of Radio, Film and Television prepared a new version of the draft, and on December 25, 2001, the Standing Committee of the State Council approved the amendments and issued a new version of the Film Administration Regulations, which came into effect on February 1, 2002, and repealed the 1996 version.: p.29–30

The 2001 regulations already require studios to conduct self-censorship when preparing their productions, and after self-censorship, scripts must be submitted to the SARFT for the record. The film must be submitted for review and approval before it is issued with a Film Public Screening Permit.: p.58–59

After 2015, China strengthened the standards of control over film legislation. On October 12, 2015, the NPC's Committee on Science, Education, Culture and Health deliberated on the draft proposed by the State Council at the NPC Standing Committee. After three deliberations, in October 2016, the 12th NPC Standing Committee confirmed that it could be adopted with one amendment, and on November 3, 2016, a meeting was held to conclude the matter. The passage of the Film Industry Promotion Law is getting closer and closer.: p.76–82

In January 2017, the SARFT issued a notice to its affiliated units throughout China to promote the Law, and on March 1, the Film Industry Promotion Law came into effect.: p.84

= 2018 to present

=In March 2018, the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party decided its publicity department would centralize the film management, taking that responsibility away from SAPPRFT, the latter of which was renamed National Radio and Television Administration. In April 2018, the department formally put up a China Film Administration sign. The consequences of this institutional change soon became apparent for industry insiders. Instead of resisting the Chinese state, they were induced to collaborate and practice "complicit creativity," which entails concession, reconfiguration, and collusion.

Indian films were de facto banned from theatrical release in China in 2020 and 2021 due to border skirmishes in addition to the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.

On June 11, 2021, the Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region announced that effective that day that it would begin censoring films according to the requirements from Hong Kong national security law, bringing itself more in line with the rest of the country.

In July 2024, the China Film Administration announced that all short films may only appear at foreign film festivals or exhibitions if they obtain permits for public screenings.

Film public screening permit

The Film Public Screening Permit (Chinese: 电影公映许可证) is issued by the Chinese film censorship department. Since July 1, 1996, films shot locally in China and films imported from abroad must be reviewed and filed in China before they can be released.: 29

According to the Motion Picture Association of America's handbook, Hollywood producers who want to co-produce with Chinese must also apply for a permit before they can be released in China.

Quota for foreign films

The Chinese censorship department's restrictions on the importation of foreign films were also under pressure from the United States,: p.67–68 and China's position in the post-Cold War world had to be recognized by the United States. In 1999, China and the United States reached a bilateral agreement on WTO accession, and all countries except the United States opposed the inclusion of film and television products in the WTO's General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade. However, with Hollywood's lobbying group pushing China to neither obey nor ignore this rule, China increased the quota for foreign films in accordance with the U.S.-China agreement. Just before the agreement was reached, the U.S. bombing of the Chinese Embassy in Yugoslavia resulted in a five-month ban on U.S. films in China.: p.53–55

In February 2012, China and the U.S. signed the Memorandum of Understanding between China and the U.S. on the Resolution of WTO Film-Related Issues (the U.S.-China Film Agreement), based on the 1999 agreement. The main content of the agreement is that the import quota for 20 Hollywood films can be unchanged, and 14 commercial films (3D or IMAX) can be added.: p.67–68

The passage of the Film Industry Promotion Act was the cause of China's anti-WTO lawsuit. Back in April 2007, the U.S. requested China to lift restrictions on the import of movies, music and books. After unsuccessful negotiations, the U.S. requested the WTO to establish a trade dispute resolution panel. In December 2009, the Appellate Body upheld the decision, finding that China's restrictions violated WTO member states' obligations and could not be justified on the grounds of protecting public morals. That is, China did violate the restrictions on U.S. entertainment products. China's appeal on the grounds of protecting its citizens, especially minors, from harmful information such as pornography was not accepted. The BBC also reported that if China does not change its current practices within two years, the U.S. has the right to request WTO authorization to impose trade sanctions on China.: p.67–68

List of suspected banned or unreleased films

Below are films that may be banned or self-censored and not released. For official bans and specific reasons at the government level, see List of films banned in China.

List of edited films

= Run time shortened by the producer and/or the distributor to ensure the profit of Chinese movie theaters

=See also

Chinese censorship abroad

List of TV and films with critiques of Chinese Communist Party

Note

Original Titles in Chinese.

References

Bibliography

Teo, Stephen (2009). "Reactions Against the Wuxia Genre". Chinese Martial Arts Cinema: The Wuxia Tradition. Edinburgh University Press. pp. 38–53. ISBN 978-0748632862.

Bai, S. (2013). Recent developments in the Chinese film censorship system [PDF file]. Retrieved from https://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1478&context=gs_rp.

Canaves, S. (2016). Trends in Chinese film law and regulation. ChinaFilmInsider. Retrieved from http://chinafilminsider.com/trends-in-chinese-film-law-and-regulation/.

GBTIMES Beijing. (2017). China launches first film censorship law. GBTimes. Retrieved from https://gbtimes.com/china-launches-first-film-censorship-law.

Weiying Peng (2015). "3" (PDF). China, Film Coproduction and Soft Power Competition (doctor thesis). Queensland University of Technology. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 3, 2018. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

Further reading

Cheng, Jim (November 2004). An Annotated Bibliography of Chinese Film Studies. Hong Kong University Press. p. 416. ISBN 9789622097032. Retrieved July 3, 2017.

Fang, Jun (2024). "The Culture of Censorship: State Intervention and Complicit Creativity in Global Film Production". American Sociological Review.

Johnson, Matthew D. (2012), "Propaganda and Censorship in Chinese Cinema", in Zhang, Yingjin (ed.), A Companion to Chinese Cinema, Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 153–178, ISBN 9781444330298

Shambaugh, David (January 2007). "China's Propaganda System: Institutions, Processes and Efficacy". The China Journal. 57 (57): 25–58. doi:10.1086/tcj.57.20066240. S2CID 222814073.

R.E (February 3, 1937). "U. S. Film Co. at Odds with Chinese Censors". Far Eastern Survey. 6 (3): 36. doi:10.2307/3021935. JSTOR 3021935.

Wall, Michael C. (2011). "Censorship and Sovereignty: Shanghai and the Struggle to Regulate Film Content in the International Settlement". Journal of American-East Asian Relations. 18: 37–57. doi:10.1163/187656111X577456.

Wang, Chaoguang (2007). "The Politics of Filmmaking: An Investigation of the Central Film Censorship Committee in the Mid-1930s". Frontiers of History in China. 2 (3): 416–444. doi:10.1007/s11462-007-0022-8. S2CID 195070026.

Xiao, Zhiwei (1997), "Anti-Imperialism and Film Censorship During the Nanjing Decade, 1927-1937", in Lu, Sheldon Hsiao-peng (ed.), Transnational Chinese Cinemas: Identity, Nationhood, Gender, Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, ISBN 9780824818456

Zhang, Rui (2008). Cinema of Feng Xiaogang : Commercialization and Censorship in Chinese Cinema After 1989. Hong Kong University Press. ISBN 978-9622098862.

External links

Works related to Regulations on the Administration of Movies at Wikisource

The dictionary definition of censorship at Wiktionary